Erik Erickson a well-known psychologist placed our need to trust first on the scale of our most basic needs and the foundation of all later development and growth. For many people, an inability to trust is to live a life of torment and aloneness. It means never allowing oneself to engage in a relationship that includes the sweetness of closeness and intimacy. One is able to avoid the vulnerability and potential for deceit or hurt, but in not trusting, one also misses the pleasures of emotional connection and deep human contact. On the other hand, trusting too readily or blindly can lead to equal suffering, anguish and pain. Then we open to the possibility of betrayal before we are sure we can trust, and betrayal is one of the most painful of human experiences. In fact, Dante, in his Divine Comedy placed the Betrayers in the inner circle of the Inferno.

Psychological studies have shown that betrayal undermines our self-confidence, sense of balance and feelings of self-worth. We actually become more self-critical when we’re betrayed by someone we love or depend on. (“Interpersonal betrayal and cooperation: Effects on self-evaluation in depression.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Feb. 1986).

The novel Trust Me by Ravindra Rajashree has become one of the most popular books in India and

around the world. It’s comic and yet serious as situations of trust are explored. The book title Trust Me comes from an old joke that is quoted in the novel: [5]

‘You didn’t let me open your hand in the beginning, and even when you did, you opened it very slowly – that shows that you don’t trust easily,’ he said.

‘You’re too closed as a person. Open up, you’ll enjoy life more.’

I took my hand back from him and lit a cigarette.

‘Do you know what “trust me” means in Polish?’ I asked.

He shook his head.

‘What?’

“‘Fuck you.’”

He laughed. I smiled.

‘So, when a guy says “trust me”,’ I said to him, ‘a warning bell rings in my head.’

He made a face. ‘Why are you so hard, so defensive?’

‘Have to be, living in Bombay, alone.’

In the dialogue above, Rajashree shows us that when asked to trust the protagonist closes her hand and shuts down. One reaction when trust is required is to withdraw. Often, when trust situations occur, a dichotomy of trusting too little or too much presents itself. Knowing when it is safe to trust and when trusting is likely to be successful, is difficult, especially in personal relationships. Roger Jackson, a Stockton State College professor in NJ offers a definition of betrayal and two guidelines that serve us well when deciding whether or not to extend our trust, whether we’re in Bombay or anywhere else in the world.

Jackson’s paper, “The Sense and Sensibility of Betrayal: Discovering the Meaning of Treachery through Jane Austen.” defines betrayal as a violation of trust and offers the following definition of trust: Trust is a situation in which the trusting person extends to another power over something he or she values with the confident expectation that the person being trusted will have the good will and competence to successfully care for it.” So in cases of interpersonal trust, such as an intimate relationship, or a relationship between doctor and patient or even in situations of simple trust such as hiring a contractor, or trusting a family member to perform a task the two questions one must satisfy in order to successfully trust are:

- Does the person have good will in caring for the object of one’s trust?

- Is the person competent to care for the object of one’s trust?

What is meant by good will and how do we know if the trusted person has it? We know mostly by what our senses tell us. We are trying to glean whether the trusted person seems to want to do the job, or if there is a sense that at least he or she is on board with what is being asked. We want to believe that there is a positive willingness to care for the object of the trust or an energy of positive intention. If we consider trusting someone, do we have a sense of the trusted person having a likely disposition to do what is being asked? Is there a desire to fulfill the expectation of caring for the trust object or a determination to do so or a desire to meet the attitude of the trust being invested?

How do we understand competence when thinking of trusting someone? In other words, does the person being trusted have what it takes to carry out the care of the valued object? How skilled or qualified is he or she? In a doctor/patient situation the doctor’s qualifications are usually known, if we are willing to look into them. But, how can the doctor trust the patient to know if he or she is competent enough to carry out the treatment steps? Or, does a spouse have the good will and/or competence to help his [or her] partner in the treatment goals? In intimate relationships, how does one know what the other person is capable of in the way of sustaining and caring for a loving relationship?

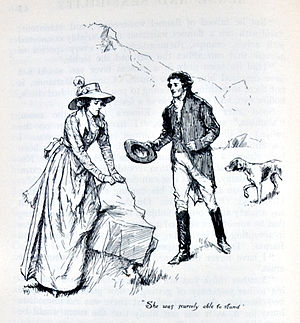

In Jane Austen’s novel Sense and Sensibility, Marianne,

who loves Willoughby deeply, feels deceived and abandoned by him, when he abruptly leaves her for another, wealthier woman. She did not recognize in his exciting implications of promised marriage, the lack of good will. She also did not see his lack of competence in being able to live without extensive wealth. Was he lying when he implied his love would lead to marriage? Sometimes we “hear” or believe what we want to hear.

In a paper called “Shakespeare’s Liars”, Inga-Stina Ewbank quotes Shakespeare talking of the “tongue”–of the deceiver throughout his plays. Shakespeare refers to the deceptive tongue as ‘double’, or’ candied’ or ‘poisoned’ — but, Ewbank says, he is equally concerned with “the ear” or how we hear what is said. Shakespeare shows repeatedly (Hamlet, Troilus and Cressida, etc.) that we can be seduced. We can have our mind, or ‘imagination’ be stimulated by what we want to hear until our ear (or our mind) is just as “infected” as the trusted person’s tongue. We begin to believe that more is promised than actually was. Then, it’s a shock when a “felt-betrayal” is denied by the betrayer–“I never told her that!” Indeed, it may never have been explicitly stated. Through verbal innuendos, it’s likely that the good will was absent, replaced by indifference if not an actual intention to deceive. Still, the implications may have flowered in the receiver’s mind, with devastating consequences.

Of course, on occasion there are extenuating circumstances. “Competency” and “good will” cannot always be perfect predictors of trust. Circumstances and the context of a situation can also interfere with the best and truest of intentions. E.g. A plan is made to vacation in a special place and illness prevents it from happening. Or, in Jane Austen’s novel, Dashwood offers to leave money in his will but the money is lost and the family he would have left it to are impoverished despite his promise to care for them after his death.

In conclusion, outside of extenuating circumstances, when we ignore our felt-sense that signals caution, like Rajashree’s warning bell, and trust in spite of those signals we may be developing an “infected ear” and colluding with the trusted person’s “double” or “candied” tongue. Too often, it leads to a kind of self-betrayal along with the other’s deception.

Instead, asking these two questions (Is the person to be trusted competent to care for the object of the trust? Does he or she have good will in relation to the care of the trust object?) and believing in the reliability of your inner response can provide a guide to increasing confidence in expectations of others. It may also help bridge the gap between trusting too much or too little and lead to happier and more successful trust experiences.

As an exercise, think back over your own situations of disappointment, feelings of betrayal or abandonment. Would these guidelines have helped to be clearer in the situation(s)? Please feel free to comment.